Above Left: Edwin Forrest as Rolla in Pizzaro, in a black-and-white photo of the portrait by John B. Neagle (1796-1865). Above Right: Engraving of the Neagle portrait by A.R. Durand, commissioned by F. Wemyss.

Pizzaro was a play adapted from the drama entitled Die Spanier in Peru by German writer August von Kotzebue (1761-1819). English playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan's adaptation was famous in England, but in America the version usually performed was by William Dunlap. In the play the young Rolla, a Peruvian native, opposes the invading Spanish. Like Young Norval, it was regarded as a suitable role for the development of a rising young leading actor. The large necklace and images of the Sun that Rolla is wearing were meant to indicate the character's Incan heritage.

Below: A portrait of the actor John Henry Erskine (1770-1830) in the role of Young Norval in Douglas, by John Home. The engraving by Edward Mitchell, after a portrait by John Singleton, and the heroic young man is wearing garb appropriate to his national heritage, too. Telling a story of an indigenous leader opposing an invading force of oppressive foreigners, and costuming him in appropriate national garb, was a very popular trope in late 18th-early 19th century drama.

Although this is a portrait of another actor, and not Forrest, I've used it for the cover art for this episode anyway. The reproductions that I can find online of the Neagle portrait (of Forrest as Rolla) done in 1826 is just too crude and muddy to be compelling as an iconic image in the digital world we live in. But the other thing that strikes me is how similar Neagle's 1826 rendering of the face of Edwin Forrest as Rolla is to Singleton's portrait of Erskine as Young Norval. Perhaps Neagle, rushed for time and remembering Forrest's earlier appearance as Young Norval, just borrowed from the older image of another actor in the role. The face in Neagle's painting doesn't really much resemble the images we have of Forrest from later years.

As we mention in the podcast, the role of Young Norval in Douglas was regarded as a proper role to test the mettle of young leading men on the English-speaking stage in the late 18th and early 19th Century. Learning his famous speech was a first step in many a young gentleman's elocution lessons, especially those from Scotland or of Scottish heritage.

The playwright, John Home (1722-1808), was a Scottish clergyman, author, and soldier. He intended the play to be an improvement on Shakespeare, who was regarded in the 18th century by many people as too rough and antiquated for modern performances. When the play was first performed in Edinburgh in 1756, the role of Young Norval was played by a "Mr. Digges". The success of the production was a local sensation, and it inspired the Caledonian taunt of English drama: "Whaur's Yer Wullie Shakespeare Noo?" Nonetheless, it was often performed South of the Border, and many English actors, including William Warren and Edmund Kean, would eventually get their start as Young Norval. The play was a natural text for a Scots teacher of elocution to bring to the attention of a young Edwin Forrest, whose father was from the countryside near Edinburgh.

We also mention in the episode that 14 year-old Edwin Forrest sampled 'laughing gas' at a public demonstration, leading to his discovery as an actor. In case anyone should think it odd that a "Professor" was showing off the effects of nitrous oxide at the Tivoli Gardens in Philadelphia in 1820 for entertainment . . . "Laughing Gas" had been used in public demonstrations, scientific lectures, and even parties in England and America for decades. Ever since the gas was first discovered by chemist Joseph Priestly in 1772, it had recreational uses. But 1799 'laughing gas parties' were common in British upper class society. It wasn't until 1844 that it began to be used as an anesthetic in medical and dental procedures. Nowadays it is often still used recreationally and illegally. (Below, a caricature of a Laughing Gas Party by Thomas Rowlandson.)

Here is the famous playbill of the Walnut Street Theatre from the evening of November 27th, 1820, headlined by Forrest's debut as "A Young Gentleman of Philadelphia". Note that the tragedy was followed by a ballet, Little Red Riding Hood, in which many members of the ubiquitous Durang family were performing. The final show on the bill was a domestic farce entitled Three Weeks After Marriage, and in the cast was Charles Durang. This bill was preserved in the scrapbooks of Durang, and someone has written at the bottom "first appearance of Edwin Forrest on any stage" - which is not strictly correct, if we count his childhood adventure at the Old Theatre in Southwark. The Durang scrapbooks are in the collection of the University of Pennsylvania, as part of the collection of his newspapers columns usually referred to as the History of the Philadelphia Stage, Between the Years 1749 and 1855.

Charles Durang and Edwin Forrest were close friends in the 1820s, and the actor and historian even named his son 'Edwin Forrest Durang'. (E.F. Durang, born in 1829, ended up becoming a prominent Philadelphia architect.)

After his success in Douglas, Edwin Forrest was hired again by Warren and Wood, this time to play the role Frederick in Kotzebue's Lovers' Vows. But he still did not get his name published on the bill, he was just called, "the Young Gentleman who played Douglas."

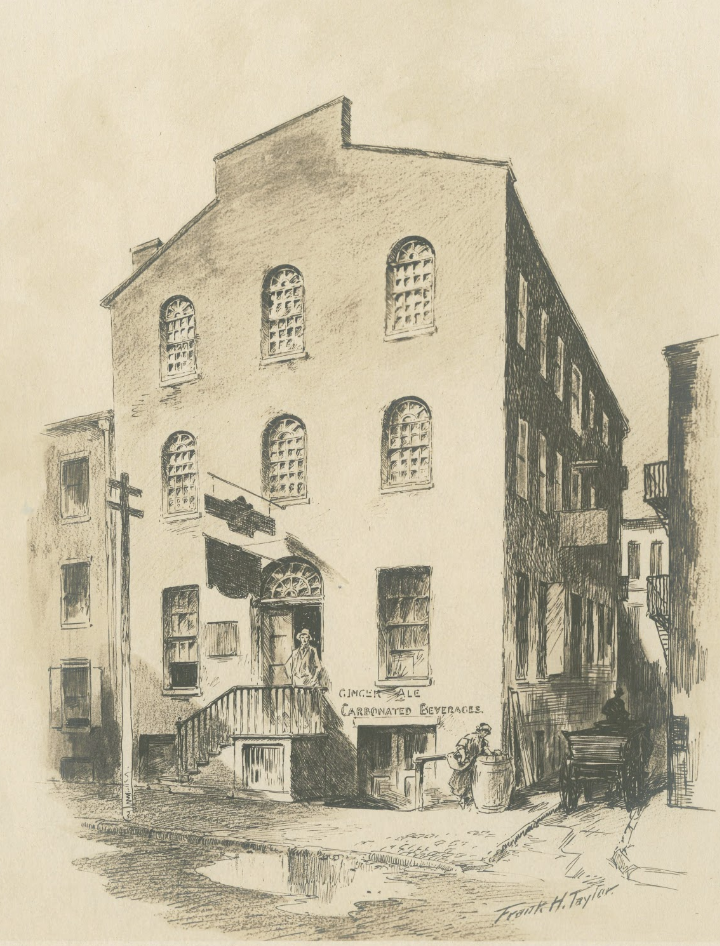

Next, the facades of three Philadelphia theaters in which Edwin Forrest performed during his early career. First, the Walnut Street Theater, as it appeared in the 1820s after it was renovated, refaced and rebuilt by architect William Strickland, in a drawing done by the artist Frank Taylor in 1920:

The short-lived Prune Street Theatre, once again re-imagined by Frank Taylor in 1920. (Prune Street was the old name for the stretch of Locust Street to the east of Washington Square). Forrest, at the age of fifteen, rented the space and performed Richard III, with a pick-up company of other young aspiring Philadelphians:

Third, the second Chestnut Street Theatre, built in 1822 on the site of the original theater destroyed by the unfortunate fire of 1820. Here Forrest would return to play Rolla in 1826. (His brother William Forrest was briefly to become the manager of the theater before his sudden death in 1834.) This image was copied from one made by William Birch in 1822.

Above, two paintings of young Edwin Forrest at about the age of twenty-two or twenty three. Both of these show Edwin in plays by James Sheridan Knowles, Virginius and William Tell. (These two roles has already been made famous in England by the young English actor William Macready. In fact, when one can see that all his career Forrest was closely emulating Macready's choice of roles and repertoire, making their future confrontation perhaps inevitable. Image of Forrest as William Tell, which I've also used at the top of this post, is from the Theatrical Collection of the University of Illinois.)

Below, a photograph from Edwin Forrest's personal collection of his beloved mother, Rebecca Lauman Forrest. She died in 1847, so given the development of photography, this was probably taken some time in the preceding ten years.

Below left, the famous engraving of James Hewlett performing Richard III in New York City that I mention during the episode. Below right, Ira Aldridge playing Othello in England.

Finally, two images from much later in Forrest's life. In 1860, Edwin Forrest posed for an extended series of photographs in the New York studio of Matthew Brady (later famous for his Civil War battlefield photographs).

Forrest, now 54 years old and by that point somewhat past the peak of his career, methodically documented almost every one of the roles that had made him famous in his youth. Below are him in costume as Othello and Rolla. We can compare these both to the image of Aldridge as Othello, and to the Neagle portrait of Forrest as Rolla from 1826. Note that Othello's hat and Rolla's necklace (like Richard III's feathers, cape, and boots) were iconic costume pieces of their time, ones that clearly signaled to the audience exactly whom the character was, no matter what actor was playing him.

Selected Bibliography:

Alger, William Rounseville, Life of Edwin Forrest, American Tragedian, J.B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia, 1876. (Available online via Project Guttenberg - https://www.gutenberg.org/files/61348/61348-h/61348-h.htm )

Bloom, Arthur W., Edwin Forrest: A Biography & Performance History, McFarland, 2019.

Bye, Arthur Edwin, "Portraits of Actors from the Collection of Edwin Forrest," Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum, Vol. 22, No. 112 (Apr., 1927), pp. 354-357.

Cliff, Nigel, The Shakespeare Riots: Revenge, Drama, and Death in Nineteenth Century America, Random House, 2007.

Davis, Andrew, America's Longest Run, A History of the Walnut Street Theatre, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010, pp. 39-80.

Douglas, a Tragedy in Five Acts by John Hone. Henry Lea, London, 1860. (Digitized 2016 and available via Google Books)

Durang, Charles, History of the Philadelphia Stage, Between the Years 1749 and 1855, Volume 2. Arranged and illustrated by Thompson Westcott, 1868. (Available online courtesy Penn Libraries, Colenda Digital Repository.)

Hill, Errol G., & James V. Hatch, A History of African American Theatre, Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 40-47.

James, Rees, The Life of Edwin Forrest, with Reminiscences and Personal Recollections, T.B. Peterson & Brothers, Philadelphia, 1874. (Digitized 2005 and available via Google Books)

Moody, Richard, Edwin Forrest, First Star of the American Stage, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1960.

Ross, Alex, "Othello's Daughter: The Rich Legacy of Ira Aldridge, the pioneering black Shakespearean", The New Yorker Magazine, July 22, 2013. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/29/othellos-daughter

Wood, William B., Personal Recollections of the Stage, Embracing Notices of Actors, Authors, and Auditors During a Period of Forty Years. Philadelphia, 1855, pp. 250-324. (Digitized 2008 and available via Google Books.)