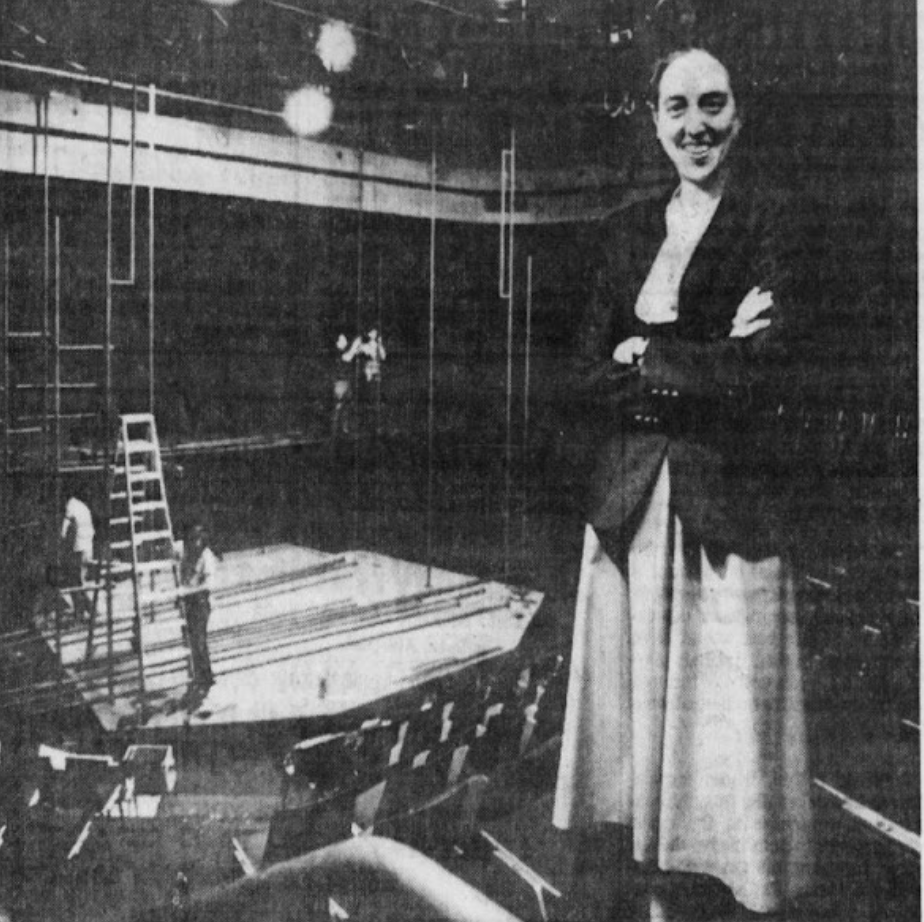

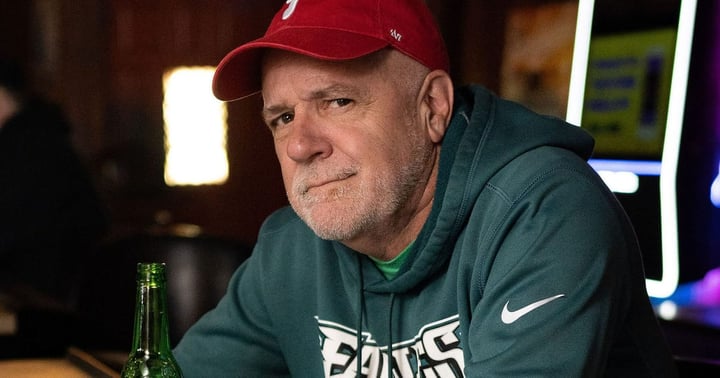

Above, a portion of a 1982 newspaper story in the Daily News, about Carol Rocamora's first season running the Philadelphia Festival Theatre for New Plays.

April 21, 1982: The Philadelphia Festival Theater for New Plays, founded almost single-handedly by Carol Rocamora, began its first season.

A series of three new plays were staged, including a new full length work by author Jack Gelber. Joseph Hart's Triple Play, three stories about baseball and American life, was the first play presented by the festival. Later would come an evening of one-act comedies, including the first play ever written by a 23 year-old New Yorker named Willie Reale.

All the shows would be presented in the 167-seat Harold Prince Theater in the Annenberg Center for Performing Arts on the Campus of the University of Pennsylvania.

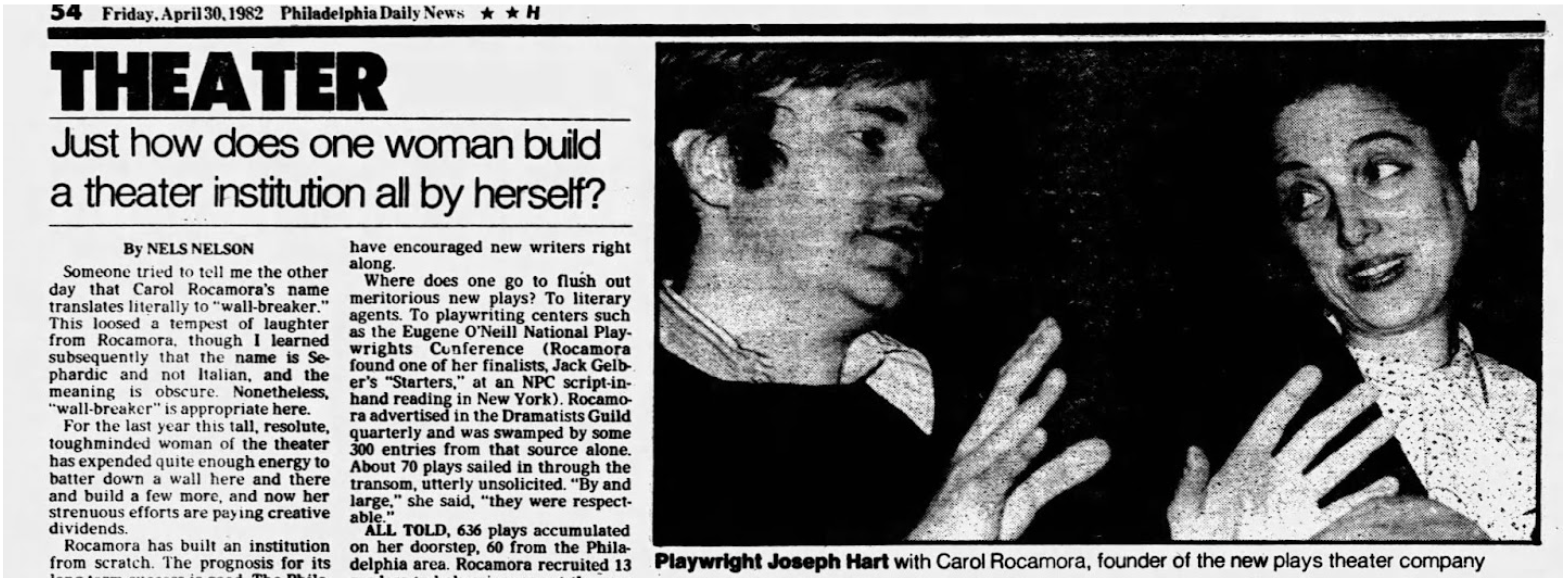

Below, another newspaper photo - this one from the Inquirer in 1984- showing Rocamora standing in the audience of the Harold Prince Theatre at the Annenberg Center, as the set is built for one of the plays of the festival's third season.

______________________________

October 22, 1987: Established Price, a play by Dennis McIntyre, opened at the Philadelphia Festival Theatre. The production had received a special grant of $50,000 from the Fund for New American Plays. The play's success was a considerable coup for the six-year-old theater company.

In the Daily News, critic Nels Nelson called it a "taut and heartfelt drama." The play was set "in the prevailing world of industrial takeovers," and focused "passionately on the hardship inflicted by corporate raiders on the individuals who have invested themselves, their creativity, enterprise and sacred trust in the swallowed-up entity, often at a great cost to their personal lives."

The play had fortunate - or perhaps unfortunate - timing. Earlier that same week, on October 19th - commonly referred to as "Black Monday" - the Dow Jones Industrial average had plunged 22.6%. It remains the largest single daily drop in the history of financial markets. Around the world other markets fell precipitously as well, with an estimated loss of almost two trillion dollars. One of the many factors later pointed to by financial analysts for the crash was that the previous week, the United States House Committee on Ways and Means had introduced a bill to reduce the tax benefits for hostile takeovers, forced mergers and leveraged buyouts. NYSE traders evidently felt that the Feds were about to "take away the punch bowl" and that the party was over.

Established Price was hailed as prophetic tale that was in the league of other financial dramas of the Reagan Era, such as Other People's Money, by Jerry Sterner, The Downside by Richard Dresser, and Serious Money, by Caryl Churchill. As it turned out, the 1987 crash did not spell the end of the financial feeding frenzy. Other forces, such as financial deregulation, the coming "Tech boom," and the rise of private equity and hedge funds, continued to bring untold wealth to the investor class, while other Americans struggled. But something deeper and more seismic had clearly happened.

(McIntyre, the author of such plays as Split Second and Modigliani, died in 1990 of stomach cancer)

______________________

January 16, 1994: Uncle Vanya, with a new translation and direction by Carol Rocamora, opened at the Philadelphia Festival Theater for New Plays.

The production received a glowing review from Nels Nelson of the Daily News, who called it "a feast so beautifully and intelligently staged that it likely will reign as the standard against which I'll match all subsequent productions" of Anton Chekhov's famous play.

Nelson felt that Rocamora's translation had transformed "a 19th-century Russian text into workmanlike late 20th-century American English without a trace of pedantry . . . The stuff is absolutely fresh and certifiably pure to the contemporary ear."

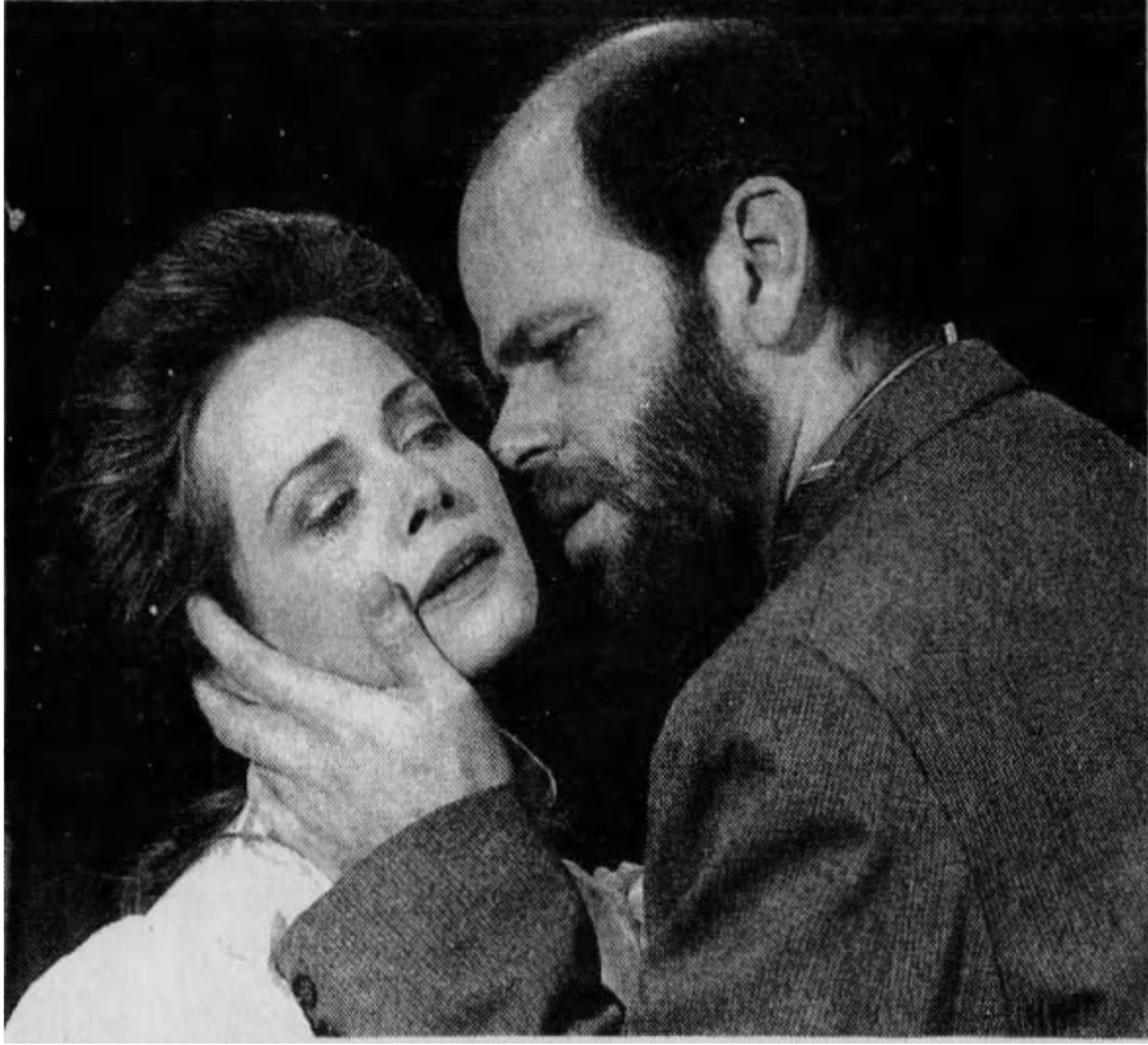

The critic also praised the work of the cast, especially Timothy Wheeler as Astrov, Lisbeth Barlett as Yelena (below), as well as Tom Teti as Vanya, Louis Lippa as Serebryakov, and Julia Gibson as Sofya. Also in the cast were such notable local talents as Katharine Minehart, Rick Stoppleworth. Jay Ansill and John Lionarons were on hand to provide Russian balalaika and violin music.

In his review in the Inquirer, Clifford Ridley likened the entire play to a string quartet, in fact, with the various roles providing "aching melodies" and "polyphonic interaction." (Though Ridley was more reserved than his colleague in his estimation of the performances and direction.)

Following up on Rocamora's previous success with her translation of The Seagull the previous year, the production of Uncle Vanya served to make the case that the classic drama could be seen as the revolutionary "new play" it had been when it was first written.

_______________________

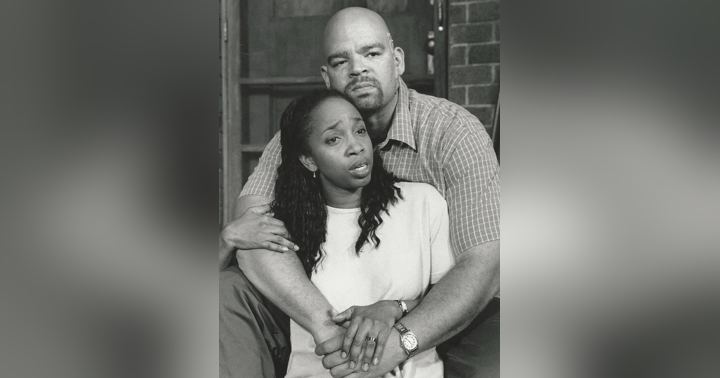

November 15, 1994: An Empty Plate in the Cafe du Grand Boeuf, a new play by Philadelphia playwright Michael Hollinger, had its world premiere at the Arden Theatre - then in its first home, the annex to St. Stephen's Church near 10th and Ludlow. The director was Terry Nolen.

There were not many top-flight restaurants in the Center City area back in those days, which was too bad, because they might have loved to advertise in the program. The play was billed as "a tragic comedy in seven courses." The cast included (L to R in the photo) Tom McCarthy, Kathleen Tague, Geoff Soffer and Jim Chance. (At the end was a surprise entrance by Sally Mercer.)

It was the third full-length play that Hollinger had written, and the first one to be fully produced. He had spent five seasons as the literary manager of the Philadelphia Festival Theatre for New Plays, and now was working part-time as the in-house dramaturg for the Wilma Theater.

That was really the best job a playwright could have, Hollinger said in an interview. "When you're working on other people's plays, you're constantly asking yourself the same questions you need to ask of yourself as a playwright: Does it work? Am I bored now? Are the characters real? How can it be made better?"

This comedy, oddly, was inspired by a co-worker's mordant jest as she left the office late one Friday evening - he might not see her Monday because she could decide to kill herself over the weekend. Fortunately, she did no such thing, but it got Hollinger to thinking about what arguments you can make in favor of Life.

It took him ten years to come up with some answers, dramatically speaking. And one of those answers, of course, was food. "Appetite is hunger with a hope," growls Victor, the main character in his play.

Critical response to the inaugural production of An Empty Plate, as it turned out, was mixed - which might be enough to make some playwrights consider suicide, but fortunately Hollinger must certainly have been cheered by the critic Clifford A. Ridley in the Inquirer, who called the show "first rate," and continued:

"An Empty Plate in the Cafe du Grand Boeuf" is set in Paris in July 1961. . . The place is the restaurant of the title (the elegant set is by Andrei W. Efremoff), which Victor owns and keeps open 24 hours a day, solely for his own use.

The staff is a memorable collection of eccentrics – Claude, the ebullient head waiter who memorizes travel brochures but never goes anywhere; his wife Mimi, contrarily bitten by wanderlust; Gaston, master of the kitchen; and Antoine, the stammering busboy who doubles as the house musician – although his only instrument is the tuba, and his total repertoire consists of "Lady of Spain." They exist solely to serve Victor . . but each of them also represents a different take on the question of hope . .

And then there is Victor himself . . He arrives in the restaurant, fresh from the bullfights in Madrid, and announces he wants nothing to eat – he plans to sit at his favorite table and starve himself to death. His resolve has something to do with a woman, and it understandably drives his minions into a panic.

And so the staff proposes a bargain. Victor will explain the roots and circumstances of his despair, as he wishes to do. Meanwhile, they will prepare a sumptuous meal, describing it as they go, and as each course is ready, they will present him with an empty plate. If Victor remains unmoved at the end of this cooked but unseen banquet, he may do as he desires. . .

Claude's florid descriptions of the food simmering in the offstage kitchen are so tempting and on-the-mark that your suspect Hollinger is either a world-class chef or has spent a lot of time writing menus. I might also note that just when you think the play is about to settle for a perfectly acceptable but rather sentimental ending, the playwright has one more trick up his sleeve . . .

"An Empty Plate in the Cafe du Grand Boeuf" is a yummy play.

_______________________