The above photograph is the graduating class of 1900 at Lincoln College (later Lincoln University) in Oxford, Pennsylvania - to the southwest of Philadelphia.

As you can see, there were some white students at Lincoln, but the large majority of students were African American. It remains as one of the leading HBUC's in the United States. The bewhiskered man in the center is Isaac Norton Rendall, the long-serving president of the college (1865 to 1906). Many African American Philadelphians at the beginning of the 20th Century were graduates of Lincoln, including both Dr. N.F. Mossell and his brother Aaron (who became a Philadelphia attorney) and his other brother Charles (who became a missionary).

The title of this post is from a chapter of historian Roger Lane’s 1991 book, William Dorsey’s Philadelphia & Ours, which discusses the role of Black professionals and the rising middle class in turn of the century Philadelphia. This book has been indispensable in my own research into the history of Philadelphia, and I am very grateful for Dr. Lane’s work.

There are two main protagonists in the episode. Let’s talk about them:

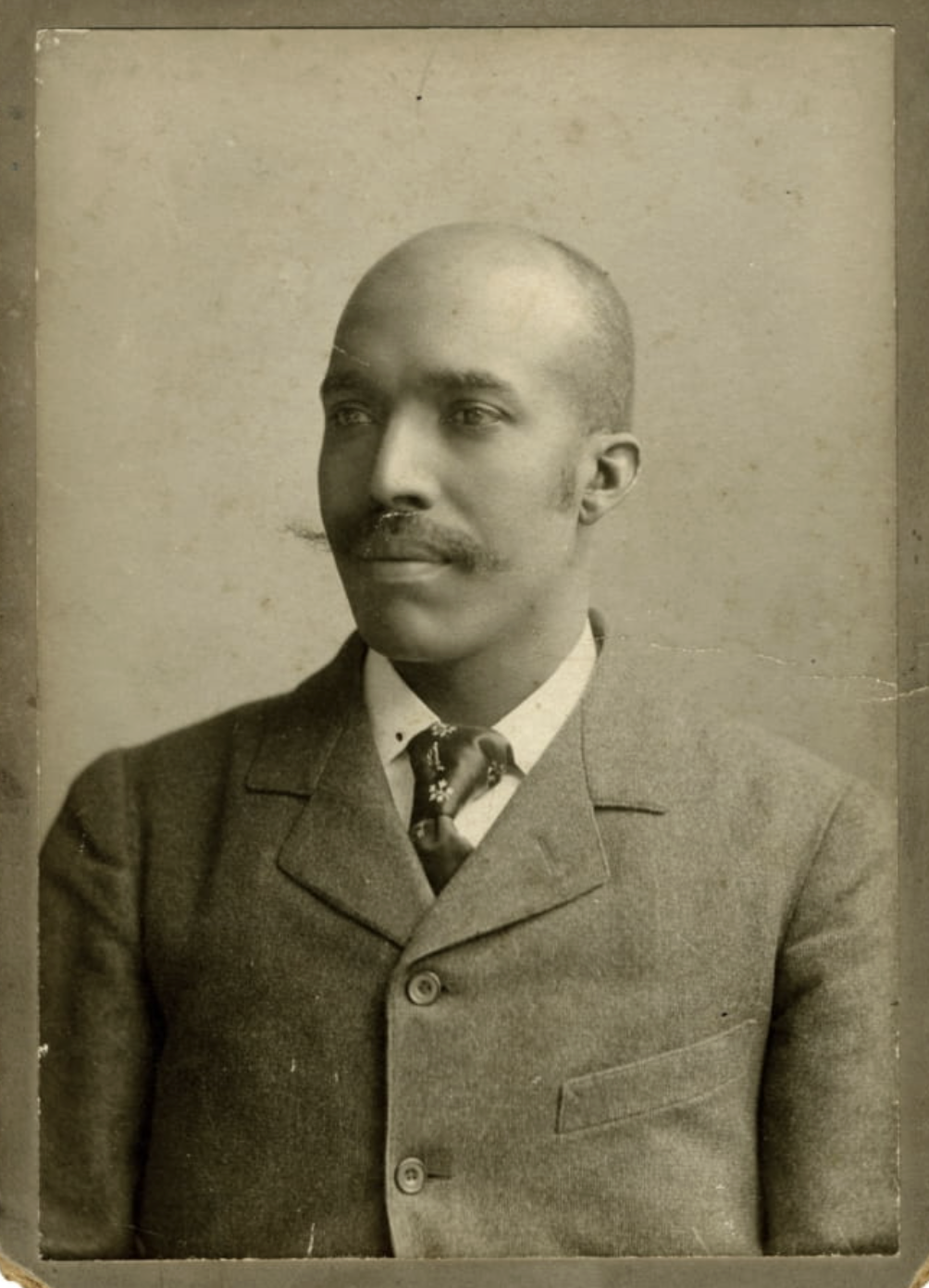

(Collection of the University of Pennsylvania Archives)

Dr. Nathan Francis Mossell (moh-SELL), as we mention in the episode, was one of the most prominent African American men in the city of Philadelphia. Born in Canada and growing up mostly in Lockport, New York, he and his brothers came to Philadelphia to get their education. After graduating from Lincoln, Nathan became the first Black man to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. During his training, it is said that sometimes he would have to attend lectures while sitting alone behind a screen, so that white students would not be “distracted” by his presence in the room.

Unable to get post-graduate training in the US because of his race, he went off to London for further study, before returning to Philadelphia and helping found the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital - the first medical institution in the city specifically meant to serve the health needs of African Americans and provide the training of Black doctors and nurses.

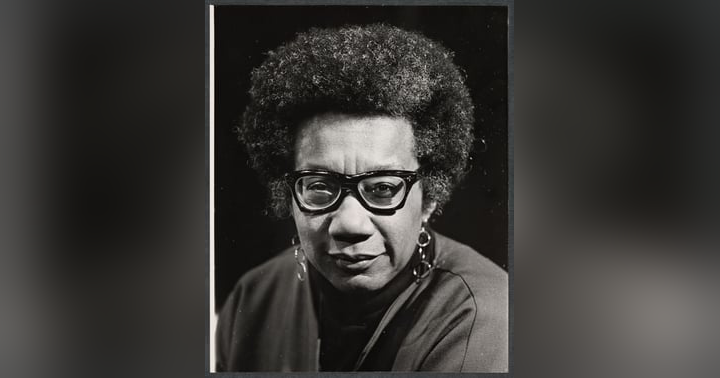

In fact, Mossell was to remain the medical director of Douglass Hospital for his entire career. In 1880 he married the journalist, author and activist Gertrude Bustill, of the prominent Bustill family. (Gertrude has an amazing story all of her own which is too long to tell here, but we should perhaps mention that her younger sister was Maria Bustill, the mother of Paul Robeson.)

Mayor John Weaver, for his part, had been born in a small town in the West Midlands of England, but had emigrated to America at the age of 20, working first as a department store clerk, he joined the congregation of Russell Conwell’s Temple Baptist Church (the institution which eventually became Temple University), and subscribed to Rev. Conwell’s doctrines of study, continuing education and advancement for working men. He studied law in the evenings and was admitted to the bar before he was thirty. He joined the city’s dominant Republican party, was elected Philadelphia’s District attorney, and was known for being a bit of a maverick and an independent. The Republicans nominated him for Mayor in 1903, as a way of staving off criticism from the calls for reform and anti-corruption efforts that, as we mentioned earlier in the podcast, were then roiling local politics. To some, of course, this made him a dangerous radical, but to Weaver he was just loyally upholding the way things were supposed to be done in his adopted country. He would leave public office in 1907 and returned to private practice until his death in 1928.

As for the other men who helped organize the fight against The Clansman, here are photos of some of the other men we mention in this episode. Clockwise, from upper left: George Henry White, Rev. G.L.P Taliaferro, Rev. Matthew Anderson, and Dr. Henry M. Minton:

George White served in the U.S. Congress as a Representative from North Carolina during the 1890s, during that brief period there when an interracial populist coalition dominated state politics. He was the first Congressman to propose Federal Anti-Lynching legislation. After he left office in 1901, there was not a single African American member of Congress for many decades thereafter. White then moved to Philadelphia, where he worked in banking.

Taliaferro was the minister of the Holy Trinity Baptist Church in Philadelphia, and was the editor of the Christian Banner, one of the oldest and most influential Black religious publications in the country. His Italian last name may seem unusual, but in fact it was very common among white slave owners in Virginia during the 19th Century as well as among the descendants of the people they enslaved. (In fact, though it is rarely mentioned, the “T.” in the name Booker T. Washington also stood for “Taliaferro.” So the two men may have been blood relatives.)

Reverend Anderson was a graduate of Oberlin College and Princeton Theological Seminary, and in the early 20th Century he was the minister of the Berean Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. In addition to his work as a pastor, he was a pioneer in linking economic development to social and civil rights for African Americans. I highly recommend the online article by Rev. Matt Leitzen about Anderson, which is listed in the bibliography below.

Dr. Henry McKee Minton was educated at Howard University, Phillips Exeter Academy, the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy - where he was one of the founders of the influential Black fraternity Sigma Pi Phi. He was the grandson of “Colonel” John McKee, one of the wealthiest Black men in Philadelphia. The Colonel was also a famous miser, and when he died in 1902 very little of his money went to his family. Minton eventually was able to secure some of it, and used it to complete his education at Jefferson Medical School. Though he worked closely with Dr. Mossell, after the events of this episode, he became a founder of Mercy Hospital, the second Black hospital in Philadelphia.

The reason I go into such detail about the educational and professional attainments of all these men is not only because they all fought and worked together against The Clansman. Their very lives and careers were also living refutations of the racist beliefs that were widely shared by many people in America in 1906 - ones that were at the very core of Thomas Dixon’s work. Dixon stated frequently that although Black people could benefit from “Western Civilization” and Democracy, they could never really join it. (What Dixon really feared was that these accomplished Black men would attempt to marry white women, as the "mulatto" character Silas Lynch tries to do in The Clansman) Like many other white people of his day, Dixon publicly stated that all Black people should be encouraged to leave the United States for Africa.

It is fascinating to note that Dr. Mossell’s own family story was deeply tied up in ‘Back to Africa’ movement. Both of his grandfathers had left North America for a period under the auspices of re-colonization organizations, but then had returned. But even Lincoln University was founded by Pennsylvania Quakers of the American Colonization Society, who supported "Back to Africa" campaigns. Indeed in 1865 they adopted its name to that of the slain President, because for many years Abraham Lincoln had held much the same views. This was a fact that Thomas Dixon Jr. never failed to gleefully point out - both in his speeches and in the original novel The Clansman. The idea was that an educated Black elite could someday be the leaders of a new African nation populated by resettled Black Americans. And indeed, this is how the country of Liberia in West Africa was founded in the 19th Century.

But Mossell had come to develop a distaste for the foundations of this theory - he had even rejected scholarships for his education from white-sponsored charities that would have required him to give sanction to it. He had many reasons to fight against people like Thomas Dixon, Jr. Not only did he strive to preserve the physical safety and health of his people, he was engaged in a lifelong struggle to assert their status as citizens of the United States, and would continue to do so, up until his death at the age of 90.

Selected Bibliography:

Newspaper articles, in chronological order :

“A Dixon Pamphlet Stirs Negro Clergy,” New York Times, December 18, 1905, p. 4.

“Hot Talk in Church After Dixon Spoke,” New York Times, Jan 29, 1906, p. 4.

“Dramatic Censor in Kentucky,” Des Moines Register, April 7, 1906, p. 4.

“The Cream of the Race’s News,” Cleveland Gazette, April 14, 1906.

“Three New Plays Unfolded Last Night,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 24, 1906, p. 6.

“Mayor Rebukes Colored Citizens,” Evening Bulletin, October 23, 1906, p 1.

“Race Riot Caused by a Press Agent,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 24, 1906, p. 7.

“Mayor Stops Play,” The North American, October 24, 1906, p. 1.

“Asks Injunction to Reverse Mayor,” Evening Bulletin, October 24, 1906, p. 1.

“Clansman Causes Strike,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 25, 1906, p. 6.

Books and Articles, alphabetical, by author:

Cook, Raymond A., Thomas Dixon, (Twayne’s United States Authors Series, Sylvia E. Bowman, ed.), Indiana University, Twayne Publishers Inc, 1974.

Lane, Roger, William Dorsey’s Philadelphia & Ours: On the Past and Future of the Black City in America, Oxford University Press, 1991.

Lehr, Dick, The Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Filmmaker and a Crusading Editor Reignited America’s Civil War, Public Affairs, New York, 2014.

Leitzen, Matt (Rev.), “A Mosaic in the Making: The Indefatigable Hope of Rev. Matthew Anderson, D.D.”, The Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation and Culture on The Washingtonist (website). https://washingtoninst.org/a-mosaic-in-the-making-the-indefatigable-hope-of-rev-matthew-anderson-d-d/

Miller, Kelly, As To The Leopard’s Spots; An Open Letter to Thomas Dixon Jr., Keyworth Publishing, Washington DC, 1905.

Slide, Anthony, American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon, The University Press of Kentucky, 2004.